Diabetes

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a set of related diseases in which the body cannot regulate the amount of sugar (specifically, glucose) in the blood.

The blood delivers glucose to provide the body with energy to perform all of a person’s daily activities.

- The liver converts the food a person eats into glucose. The glucose is then released into the bloodstream.

- In a healthy person, the blood glucose level is regulated by several hormones, primarily insulin. Insulin is produced by the pancreas, a small organ between the stomach and liver. The pancreas also makes other important enzymes released directly into the gut that helps digest food.

- Insulin allows glucose to move out of the blood into cells throughout the body where it is used for fuel.

- People with diabetes either do not produce enough insulin (type 1 diabetes) or cannot use insulin properly (type 2 diabetes), or both (which occurs with several forms of diabetes).

- In diabetes, glucose in the blood cannot move efficiently into cells, so blood glucose levels remain high. This not only starves all the cells that need the glucose for fuel, but also harms certain organs and tissues exposed to the high glucose levels

Types of Diabetes

Type 1 diabetes (T1D): The body stops producing insulin or produces too little insulin to regulate blood glucose level.

- Type 1 diabetes involves about 10% of all people with diabetes in the United States.

- Type 1 diabetes is typically diagnosed during childhood or adolescence. It used to be referred to as juvenile-onset diabetes or insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus.

- Type 1 diabetes can occur in an older individual due to destruction of the pancreas by alcohol, disease, or removal by surgery. It also results from progressive failure of the pancreatic beta cells, the only cell type that produces significant amounts of insulin.

- People with type 1 diabetes require insulin treatment daily to sustain life.

Type 2 diabetes (T2D): Although the pancreas still secretes insulin, the body of someone with type 2 diabetes is partially or completely unable to use this insulin. This is sometimes referred to as insulin resistance. The pancreas tries to overcome this resistance by secreting more and more insulin. People with insulin resistance develop type 2 diabetes when they fail to secrete enough insulin to cope with their higher demands.

- At least 90% of adult individuals with diabetes have type 2 diabetes.

- Type 2 diabetes is typically diagnosed in adulthood, usually after age 45 years. It used to be called adult-onset diabetes mellitus, or non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. These names are no longer used because type 2 diabetes does occur in younger people, and some people with type 2 diabetes require insulin therapy.

- Type 2 diabetes is usually controlled with diet, weight loss, exercise, and oral medications. However, more than half of all people with type 2 diabetes require insulin to control their blood sugar levels at some point in the course of their illness.

Complications of Diabetes

Both type 1 and type 2 diabetes ultimately lead to high blood sugar levels, a condition called hyperglycemia. Over a long period of time, hyperglycemia damages the retina of the eye, the blood vessels of the kidneys, the nerves, and other blood vessels.

- Damage to the retina from diabetes (diabetic retinopathy) is a leading cause of blindness.

- Damage to the kidneys from diabetes (diabetic nephropathy) is a leading cause of kidney failure.

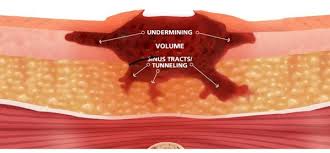

- Damage to the nerves from diabetes (diabetic neuropathy) is a leading cause of foot wounds and ulcers, which frequently lead to foot and leg amputations.

- Damage to the nerves in the autonomic nervous system can lead to paralysis of the stomach (gastroparesis), chronic diarrhea, and an inability to control heart rate and blood pressure during postural changes.

- Diabetes accelerates atherosclerosis, (the formation of fatty plaques inside the arteries), which can lead to blockages or a clot (thrombus). Such changes can then lead to heart attack, stroke, and decreased circulation in the arms and legs (peripheral vascular disease).

- Diabetes predisposes people to elevated blood pressure, high levels of cholesterol and triglycerides. These conditions both independently and together with hyperglycemia, increase the risk of heart disease, kidney disease, and other blood vessel complications.

Diabetes Causes

Type 1 diabetes: Type 1 diabetes is believed to be an autoimmune disease. The body’s immune system specifically attacks the cells in the pancreas that produce insulin.

- A predisposition to develop type 1 diabetes may run in families, but genetic causes (a positive family history) are much more common for type 2 diabetes.

- Environmental factors, including common unavoidable viral infections, may also contribute to type 1 diabetes.

- Type 1 diabetes is most common in people of non-Hispanic, Northern European descent (especially Finland and Sardinia), followed by African Americans, and Hispanic Americans. It is relatively rare in those of Asian descent.

- Type 1 diabetes is slightly more common in men than in women.

Type 2 diabetes: Type 2 diabetes has strong genetic links, meaning that type 2 diabetes tends to run in families. Several genes have been identified, and more are under study which may relate to the causes of type 2 diabetes. Risk factors for developing type 2 diabetes include the following:

- High blood pressure

- High blood triglyceride (fat) levels

- Gestational diabetes or giving birth to a baby weighing more than 9 pounds

- High-fat diet

- High alcohol intake

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Obesity or being overweight

- Ethnicity, particularly when a close relative had type 2 diabetes or gestational diabetes: certain groups, such as African Americans, Native Americans, Hispanic Americans, and Japanese Americans, have a greater risk of developing type 2 diabetes than non-Hispanic whites.

- Aging: Increasing age is a significant risk factor for type 2 diabetes. Risk begins to rise significantly at about age 45 years, and rises considerably after age 65 years.

Diabetes Symptoms

Symptoms of type 1 diabetes are often dramatic and come on very suddenly.

- Type 1 diabetes is usually recognized in childhood or early adolescence, often in association with an illness (such as a virus or urinary tract infection) or injury.

- The extra stress can cause diabetic ketoacidosis.

- Symptoms of ketoacidosis include nausea and vomiting. Dehydration and often-serious disturbances in blood levels of potassium follow.

- Without treatment, ketoacidosis can lead to coma and death.

Symptoms of type 2 diabetes are often subtle and may be attributed to aging or obesity.

- A person may have type 2 diabetes for many years without knowing it.

- People with type 2 diabetes can develop hyperglycemic hyperosmolar nonketotic syndrome.

- Type 2 diabetes can be precipitated by steroids and stress.

- If not properly treated, type 2 diabetes can lead to complications such as blindness, kidney failure, heart disease, and nerve damage.

Common symptoms of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes include:

- Fatigue, constantly tired: In diabetes, the body is inefficient and sometimes unable to use glucose for fuel. The body switches over to metabolizing fat, partially or completely, as a fuel source. This process requires the body to use more energy. The end result is feeling fatigued or constantly tired.

- Unexplained weight loss: People with diabetes are unable to process many of the calories in the foods they eat. Thus, they may lose weight even though they eat an apparently appropriate or even an excessive amount of food. Losing sugar and water in the urine and the accompanying dehydration also contributes to weight loss.

- Excessive thirst (polydipsia): A person with diabetes develops high blood sugar levels, which overwhelms the kidney’s ability to reabsorb the sugar as the blood is filtered to make urine. Excessive urine is made as the kidney spills the excess sugar. The body tries to counteract this by sending a signal to the brain to dilute the blood, which translates into thirst. The body encourages more water consumption to dilute the high blood sugar back to normal levels and to compensate for the water lost by excessive urination.

- Excessive urination (polyuria): Another way the body tries to rid the body of the extra sugar in the blood is to excrete it in the urine. This can also lead to dehydration because a large amount of water is necessary to excrete the sugar.

- Excessive eating (polyphagia): If the body is able, it will secrete more insulin in order to try to manage the excessive blood sugar levels. Moreover, the body is resistant to the action of insulin in type 2 diabetes. One of the functions of insulin is to stimulate hunger. Therefore, higher insulin levels lead to increased hunger. Despite increased caloric intake, the person may gain very little weight and may even lose weight.

- Poor wound healing: High blood sugar levels prevent white blood cells, which are important in defending the body against bacteria and also in cleaning up dead tissue and cells, from functioning normally. When these cells do not function properly, wounds take much longer to heal and become infected more frequently. Long-standing diabetes also is associated with thickening of blood vessels, which prevents good circulation, including the delivery of enough oxygen and other nutrients to body tissues.

- Infections: Certain infections, such as frequent yeast infections of the genitals, skin infections, and frequent urinary tract infections, may result from suppression of the immune system by diabetes and by the presence of glucose in the tissues, which allows bacteria to grow. These infections can also be an indicator of poor blood sugar control in a person known to have diabetes.

- Altered mental status: Agitation, unexplained irritability, inattention, extreme lethargy, or confusion can all be signs of very high blood sugar, ketoacidosis, hyperosmolar hyperglycemia nonketotic syndrome, or hypoglycemia (low sugar). Thus, any of these merit the immediate attention of a medical professional. Call your health care professional or 911.

- Blurry vision: Blurry vision is not specific for diabetes but is frequently present with high blood sugar levels

Diabetes Treatment

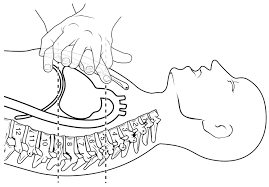

There are a variety of treatments for diabetes. Type 1 diabetes is treated with insulin injections and lifestyle modifications. Type 2 diabetes is generally treated with lifestyle changes such as diabetic diet, exercise, and medication.

Diabetes Self-Care at Home (Diet, Exercise, and Glucose Monitoring)

If a person has diabetes, healthful lifestyle choices in diet, exercise, and other health habits will help to improve glycemic (blood sugar) control and prevent or minimize complications of diabetes.

Diabetes Diet: A healthy diet is key to controlling blood sugar levels and preventing diabetes complications.

- If the patient is obese and has had difficulty losing weight on their own, talk to a health care professional. He or she can recommend a dietitian or a weight modification program to help the patient reach a goal.

- Eat a consistent, well-balanced diet that is high in fiber, low in saturated fat, and low in concentrated sweets.

- A consistent diet that includes roughly the same number of calories at about the same times of day helps the health care professional prescribe the correct dose of medication or insulin.

- A healthy diet also helps to keep blood sugar at a relatively even level and avoids excessively low or high blood sugar levels, which can be dangerous and even life-threatening.

Exercise: Regular exercise, in any form, can help reduce the risk of developing diabetes. Activity can also reduce the risk of developing complications of diabetes such as heart disease, stroke, kidney failure, blindness, and leg ulcers.

- As little as 20 minutes of walking three times a week has a proven beneficial effect. Any exercise is beneficial; no matter how easy or how long, some exercise is better than no exercise.

- If the patient has complications of diabetes (such as eye, kidney, or nerve problems), they may be limited both in type of exercise, and amount of exercise they can safely do without worsening their condition. Consult with your health care professional before starting any exercise program.