A waste is a by-product of your work or research that has no further use. If you work with chemicals, you are probably a hazardous-waste generator. A hazardous waste is any waste regulated by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Some examples of hazardous waste are:

- Flammable liquids, such as non halogenated solvents

- Corrosive liquids, such as strong acids and bases

- Wastes that contain heavy metals and halogenated organics

The first step in determining if you have a hazardous waste is to understand the materials that go into your process, how the materials are used, and how they flow into and out of the process. You must be aware of any potential reactions that might occur that could change the nature of the chemicals you are using. It is quite possible that your process could change hazardous materials into materials that are no longer hazardous, e.g., neutralization or complexing of an acid or base with a buffer compound. Though less common, you should also be aware of the potential to create hazardous materials during your process.

One important information source that can help you determine if your waste is hazardous is the Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS) for each chemical you use. Before working with any chemical, you should review the MSDS and understand the hazards of the material. More information on working with hazardous materials can be found in the Chemical Hygiene and Safety Plan. As a general rule, you should never work with hazardous materials and generate hazardous waste without being properly trained in safe handling and management practices for such work. Once you have an understanding of the materials in your waste, you can proceed to evaluate the waste as hazardous for possible regulation. Your first responsibility as a hazardous-waste generator is to complete appropriate training. The Hazardous Waste Handling Facility (HWHF) will accept waste only from generators who have completed the training course.

If any of the definitions below apply to your waste, the container must be labeled as “Hazardous Waste,” and managed accordingly. If you are unsure whether your waste is hazardous, you may simply label the waste, and then call your Generator Assistant. There is no penalty for labeling waste that may later be determined to be nonhazardous waste.

Characteristic Waste:

Characteristic waste is considered hazardous based on specific properties of the material. The four basic properties that can define a characteristic waste are ignitability, corrosivity, reactivity, and toxicity.

Ignitability:

A waste is ignitable if:

(1) it is a liquid with a flash point of less than 140°F, unless the liquid is an aqueous alcohol solution with less than 24% alcohol by volume;

(2) it is not a liquid and is capable of causing fire through friction, absorption of moisture, or spontaneous chemical changes;

(3) it is an ignitable compressed gas; or

(4) it is an oxidizer.

Examples of Ignitable Waste

Ignitable liquids: acetone, acetonic, benzene, hexanes, methanol, ethanol, isopropanol, toluene, xylene, methyl ethyl ketone, lacquer thinner.

Ignitable compressed gases: hydrogen, methane, acetylene, propane, butane, spray-paint cans.

Oxidizers: ammonium per sulfate, sodium nitrate, potassium permanganate, sodium perchlorate, hydrogen peroxide (aqueous solution greater than or equal to 8%), potassium peroxide.

Corrosivity

A waste is corrosive if:

(1) it is aqueous and has a pH ≤2 or ≥12.5, as measured by a pH meter;

(2) it is a liquid and corrodes steel at a rate greater than ¼-inch per year in a standard corrosivity test;

(3) it is not aqueous, and when mixed with an equivalent weight of water, produces a solution having a pH ≤2 or ≥12.5 (in California only); or

(4) it is not a liquid, and when mixed with an equivalent weight of water, produces a solution that corrodes steel at a rate greater than ¼-inch per year in a standard corrosivity test .

Examples of Corrosive Waste

Corrosive aqueous liquids: hydrochloric acid, sulfuric acid, nitric acid, perchloric acid, acetic acid, sodium hydroxide solution, potassium hydroxide solution.

Reactivity

A waste is reactive if:

(1) it is normally unstable and readily undergoes violent change without detonating;

(2) it reacts violently with water;

(3) it forms potentially explosive mixtures with water;

(4) it generates toxic gases, vapors, or fumes when mixed with water;

(5) it contains cyanides or sulfides and can generate toxic gases when exposed to pH conditions between 2 and 12.5; or

(6) it is explosive under standard temperature and pressure conditions, or it can explode if subjected to a strong initiating source or heated under confinement.

Examples of Reactive Waste

Sodium metal, potassium metal, lithium metal, concentrated sulfuric acid, picric acid, trinitrobenzene, metal azides, amides, benzoyl peroxide.

Toxicity

A waste is toxic if:

(1) it can release sufficient amounts of specific toxic metals or organics in standard leaching or extraction tests ;

(2) it contains sufficient total amounts of specific toxic metals, organics, or asbestos ;

(3) it has an acute oral LD50 less than 2,500 milligrams per kilogram ;

(4) it has an acute dermal LD50 less than 4,300 milligrams per kilogram;

(5) it has an acute inhalation LC50 less than 10,000 parts per million as a gas or vapor ;

(6) it has an acute aquatic 96-hour LC50 less than 500 milligrams per liter in a standard aquatic toxicity test ;

(7) it contains specific known human carcinogens in a single or combined concentration equal to or exceeding 0.001% by weight;

(8) it has been shown through experience or testing to pose a hazard to human health or the environment because of carcinogenicity, acute or chronic toxicity, bioaccumulative properties, or persistence in the environment.

Examples of Toxic Waste

Waste containing the following metals or inorganics above specific limits: antimony, arsenic, barium, beryllium, cadmium, chromium, cobalt, copper, lead, mercury, molybdenum, nickel, selenium, silver, thallium, vanadium, zinc, asbestos, fluorides.

Waste containing the following organic constituents above constituent-specific limits: benzene, carbon tetrachloride, chlorobenzene, chloroform, cresols, 1,2-dichloroethane, methyl ethyl ketone, nitrobenzene, pyridine, tetrachloroethylene, trichloroethylene, PCBs.

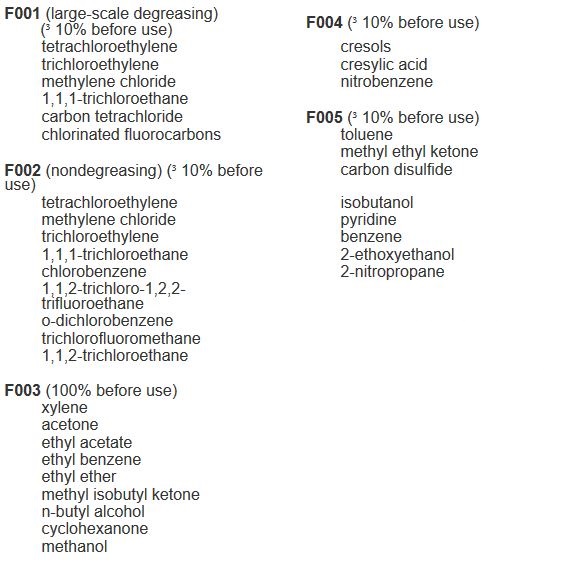

Listed Waste:

The definition of a “listed waste” is more convoluted. The listed wastes that create the most questions are typically solvents. EPA regulations require us to consider how the solvent was used in the process. EPA considers listed waste to be hazardous, regardless of its concentration or physical characteristics.

Generally, the waste generator is the only person who can provide enough information for us to make this determination. The following examples are meant to illustrate the information required by the Waste Management Group in order to comply with EPA and state regulations.

Example 1: A Waste Is Described as 50% Acetone and 50% Hexane

Case 1—Assume your experimental procedure requires that you mix acetone and hexane in a 50:50 ratio, and that this mixture is used in your process. In this case, the listed-waste criteria would not  apply, because the acetone was not at 100% before you used it in your process; instead, it was 50%. Therefore, only the characteristic criteria would apply.

apply, because the acetone was not at 100% before you used it in your process; instead, it was 50%. Therefore, only the characteristic criteria would apply.

Case 2—Suppose you use pure acetone as a solvent in one process, and pure hexane in a separate process. One day, you add 1 gallon of used or “spent” acetone to your waste container; the next day, you add 1 gallon of used or “spent” hexane. This waste is also a 50:50 mixture of acetone and hexane, but now since the acetone was at 100% when it was used in your process, the entire waste has to be managed as a listed waste.

Example 2: A Waste Is Described as 4% Methylene Chloride, 48% Phenol, and 48% Chloroform

Case 1—Assume your experimental procedure requires a mixture of methylene chloride, phenol, and chloroform in a 4:48:48 ratio prior to use in your experiment. After use, this is added to your waste container. In this case, because the methylene chloride added to the mixture was less than 10% before use, only a characteristic waste code applies.

Case 2—Assume that this mixture occurred after the experimental process. One day, 2,400 mL of a 50:50 mixture of phenol chloroform is added to your waste container. A few days later, 100 mL of used 100% methylene chloride is added to this same container. In this scenario, the entire waste container is subject to the listed-waste rule, because the concentration of methylene chloride was greater than 10% when it was added to the waste container.

These examples also illustrate the need to maintain an accurate accumulation log .Follow-up phone calls by your Generator Assistant can be minimized or avoided by doing the following:

- Review the list of chemicals in Table 1-1; use nonhazardous substitutes, if possible.

- List the concentrations of all waste constituents.

- Fax copies of detailed accumulation logs.

- Tell Waste Management if the material is used or surplus unused material.

- 5.Discuss your generating process with your Generator Assistant.

Chemical Compatibility:

Incompatible chemical wastes should never be mixed together. Uncontrolled chemical reactions may endanger your safety and the safety of those around you. The act of mixing together separate wastes may also result in a regulatory violation for unpermitted treatment. Benchtop treatment may be an alternative if your goal is to avoid mixed-waste charges or you are generating nitric acid wastes

EPA F-Listed Hazardous Wastes

F-Listed hazardous wastes include spent solvents used in degreasing or other solvent operations, and various spent solvents that are no longer useful for their original purpose.

Federal Listed Hazardous Wastes

The Importance of the Waste Generator

If you generate hazardous waste, you have an important role to play in assuring that we manage that waste in an environmentally conscious manner and in compliance with all regulations. The waste generator is the only person with reliable and credible knowledge of the waste constituents and of how the waste was created. We often have to ask questions about the waste-generating process, and the generator, not a third party, is the only source of that information.

Your first responsibility as a hazardous-waste generator is to complete appropriate training. The Hazardous Waste Handling Facility (HWHF) will accept waste only from generators who have completed

Hazardous-waste regulations dictate that you, as the generator, are responsible for the complete and accurate characterization of your waste. Precise characterization is essential to ensure

- Safe handling.

- Protection of the environment.

- Compliance with federal and state packaging requirements.

- Compliance with land-disposal restrictions.

- Acceptance of the wastes by appropriate recycling or disposal facilities.

Characterization:

Because most chemical waste is generated during specific processes in the course of your activities or experiments, you should know the chemical content of your waste from your “knowledge of the process” you used to generate it . In fact, the individual generating the waste is, in most cases, recognized as a more accurate source than certified analytical laboratories for specifying components and their concentrations in a given waste sample. Most hazardous waste generated at Berkeley Lab can be characterized through process knowledge. However, this approach must be supported by precise, documented information . To use and justify process knowledge for characterization, you must

- Know the hazardous properties of all chemicals used

- Have a thorough understanding of how the chemicals were used

- Understand the chemistry of the reaction to determine if hazardous chemicals were produced where none existed before

- Know whether the process converted hazardous chemicals to nonhazardous ones

Hazardous Waste Characterization Criteria

Once you have determined that your waste is hazardous and have identified the type(s) of hazard(s), all hazardous and nonhazardous components must be fully identified and documented. It is important to account for 100% of the contents of each waste container, including trace amounts of known hazardous components or other materials of concern (such as nanomaterials). A common problem is the failure to recognize that water and hydrogen ions (pH), if present, must be listed as components.

Hazardous-waste characterization may be achieved in the following ways:

By maintaining records (logs) of accumulation that draw upon knowledge of the procedures and processes that generated the wastes. The logs contain an entry each time a chemical is added to a container and a link to the forms. To use and justify process knowledge for containers with repetitive additions of various constituents, this record must be a timely and accurate reflection of what has been added to the container. When the container is no longer needed, this record becomes the basis to develop summaries, which will be provided as part of a pickup request. For waste that is collected in this manner, this record of accumulation must accompany all subsequent document submittals to the Waste Management Group.

By consulting an MSDS for each hazardous component, and listing quantitative information for all hazardous and nonhazardous components.

By developing a generic description when the material has a well-known standard composition (e.g., waste alkaline batteries or a broken mercury thermometer).

By using analytical results from a certified laboratory on known, unchanging waste streams (i.e., a waste profile), or by using complete analytical results from a certified laboratory for each waste. Analytical results from a noncertified laboratory may be used if adequate analytical records and procedures are documented and available to the Waste Management (WM)Group of the Environment, Health, and Safety (EH&S) Division, but will only be considered as a qualified form of your process knowledge.

Labeling of Waste Containers:

As a hazardous-waste generator, you are responsible for assuring that any container used to accumulate hazardous waste is properly labeled in order to meet regulatory requirements and assure the safety of those around you. The labeling requirement applies from the moment the first drop of waste is placed in the container. At that point, you must fill out and attach a hazardous-waste label to the waste container. Figure-1 is an example of a properly completed hazardous-waste label. If you have multiple containers of the same waste stream, each of a 60 ml size or greater, they should be labeled separately. Smaller containers (<60 mL) can be grouped together in a larger container and labeled as a unit.

The hazardous-waste label identifies:

- the waste generator,

- the contents of the container,

- information on the hazardous characteristic(s) of the waste, and

- establishes the waste-generation start date.

The waste generator must fill in the start date when the first addition is made to the waste container. Each primary waste container must have a label attached, indicating the composition of the material. A manufacturer’s label does not serve this purpose, even if proper hazard information is on the label.

All entries on the hazardous-waste label must be legible. It is recommended that entries be made with a permanent marker or a pen containing permanent ink. Ballpoint pens, pens with water-soluble ink, or pencils should not be used to fill out hazardous-waste labels. For large primary waste containers such as carboys, the hazardous-waste label should be affixed to an area of the container that is easily visible for inspection and emergency-response purposes. A waste container that is too small for a label can be placed in a ziplock plastic bag, with a hazardous-waste label affixed to the bag. If this method is used, be sure there is a very clear association between the hazardous-waste label and the actual primary waste container.

The “Contents” section of the Label can be completed using one of the following three approaches:

- By chemical name. If the material is a mixture, identify at least two or three of the major constituents that contribute to the primary hazard(s), including nonhazardous constituents, if appropriate. For waste containing nanomaterials, the description must include “contains nanomaterials.”

Examples: 1 M hydrochloric acid, aqueous solution; used acetone; contains acetone, hexane, methanol. Remember, if the composition is changing due to repetitive additions of compatible waste materials, maintain an accumulation log for the container, and record each entry on the log.

Figure 1. Example of a properly completed hazardous-waste label.

2. By manufacturer and specific product (for example, trade name or number, catalog number, etc.), including the primary hazardous materials listed in the MSDS for the specific product.

Example: BioRad protein assay dye reagent contains methanol and phosphoric acid.

Chemical identification information of manufactured products may also be found in the Aldrich Catalog of Fine Chemicals; the NIOSH Registry of Toxic Effects of Chemical Substances; and The Merck Index: An Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs, and Biologicals.

3. By complete generic description of the material, only if the material is a mixture with a well-known standard composition. The description should indicate whether the material is new, has exceeded its shelf life, is spent, etc. If the material is a process waste, such as a cleaning agent or an etching bath, list all of the potential contaminants from the process in addition to the known constituents. For machine coolants, identify the metals for which the coolants were used. The generic description must be sufficiently complete to adequately characterize the waste material.

Example: Chromic acid dip-tank waste with copper. “Photochemicals” is insufficient because a wide variety of chemicals are used in photoprocessing. The description must be more specific, such as “alkaline photo developer” or “used photo fixer with chromate bleach.”

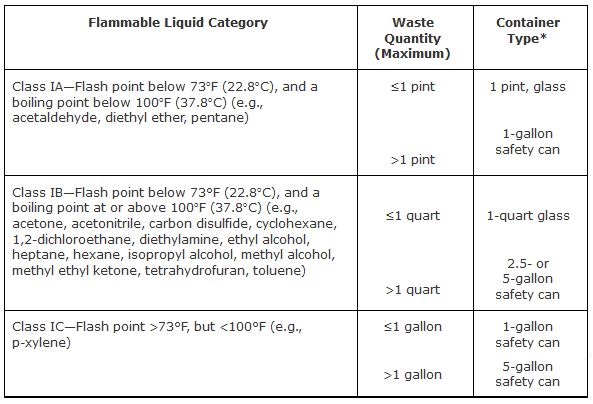

Flammable Wastes

Accumulation of flammable wastes must be in accordance with the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) and Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) safety guidelines. NFPA 45, Fire Protection for Laboratories Using Chemicals, Table-1 (2004 Edition), and OSHA 1910.106d, Table H-12 restrict the sizes and types of containers that can be used for storage of flammable liquid waste in the workplace.

Flammable or ignitable wastes may not be accumulated in plastic containers of any type other than a listed and approved safety can (Figures 2 and 3 show examples of flammable waste cans). Approved, reusable safety cans are available from the Waste Management Group in 5-, 2.5-, and 1-gallon capacities. If you have small amounts of flammable waste, glass containers may be used, but the maximum allowable waste quantity in a glass container is 1 pint for Class IA liquids, and 1 quart for Class IB liquids

Figure 2. A 5-gallon flammable waste can. Figure 3. A 2.5-gallon flammable waste can.

Figure 4. Glass bottles suitable for Class 1A flammable liquids (1 pint) or Class 1B flammable liquids (1 quart).

Table 1. Appropriate Containers for Small Quantities of Flammable Liquids

Waste Accumulation Area (WAA)

A Waste Accumulation Area (WAA) is a storage area designed for the accumulation of hazardous wastes for up to 90 days, in total quantities that can exceed 55 gallons (208 liters) of hazardous waste, 1 quart (0.946 liter) of extremely hazardous waste, or 1 quart (0.946 liter) of acutely hazardous waste. Berkeley Lab policy allows the accumulation of hazardous waste in a WAA for a maximum of 60 days to assure compliance with state regulations. This is not an HWHF Permit condition. The 60-day storage period begins on the date (called the “WAA receival date” or the “accumulation start date”) when waste is first placed in the container.

WAAs offer benefits to large-quantity waste generators. They provide a single area for the accumulation of large quantities of waste, and in the event of a spill, they prevent hazardous materials from entering the environment by means of required secondary containment. In addition, they contain emergency equipment in the event of a spill or release. The actual need for a WAA is best determined through consultation between the waste-generating organization and the Generator Assistant. A WAA cannot be established without prior EH&S approval.

The physical requirements for WAAs include:

- Secondary containment

- Shelter from the elements

- Controlled access

- Appropriate signs

- A method to separate incompatible wastes

- Sufficient access to allow pickup of waste

- A washable surface (e.g., concrete or asphalt)

Where possible, the WAA should be a distance of approximately 50 feet from sanitary sewers or storm drains. The WAA must also be located at least 50 feet from the facility property line if flammable or reactive waste is being accumulated.

The following safety equipment must be maintained at or near all WAAs:

- Portable fire extinguisher and/or fixed fire-suppression system

- Emergency spill kit

- Emergency eyewash and safety shower

- Telephone (either at the WAA or nearby, with a sign indicating the direction to the nearest phone)

- Personal protective equipment (e.g., gloves, safety glasses)

- Appropriate hazard warning signs (e.g., “Flammables,” “Hazardous Waste Area”)

- Posted contingency plan for dealing with spills and other accidental releases of hazardous wastes

- Posted names and telephone numbers (day and night) of responsible individuals (WAA manager and alternate)

Universal Wastes

Universal wastes include batteries, fluorescent lamps, aerosol cans, mercury-containing equipment, electronic devices, cathode-ray tubes, and broken cathode-ray tube glass. Because properly managed universal waste poses a lower immediate risk to people and the environment, it can be handled and transported under more relaxed rules than hazardous wastes. However, universal wastes do contain hazardous materials and must therefore be taken to a designated handler or recycler and processed in compliance with universal waste regulations.

Batteries

Waste Management provides green collection buckets for used nickel-cadmium; nonspillable, nonleaking lead acid; and alkaline batteries. Place your batteries in the green collection bucket (Figure -5). All 9-V batteries and batteries with terminals on the same side must have the leads taped to prevent the possibility of fire or sparking. The buckets are emptied once per quarter or as needed. Automotive batteries (lead acid) can be sent to salvage as long as the caps are intact and the body is not damaged or cracked. Only batteries should be placed in the green bucket. Other items such as computer parts or mercury-containing devices present safety hazards and should be collected elsewhere.

If you have leaking lead-acid batteries, these are regulated as hazardous waste and must be requisitioned in the normal process. Figure-5

Universal Waste Definition of “Battery”?

Battery means a device consisting of one or more electrically connected electrochemical cells which is designed to receive, store, and deliver electric energy. An electrochemical cell is a system consisting of an anode, cathode, and an electrolyte, plus such connections (electrical & mechanical) as may be needed to allow the cell to deliver or receive electrical energy. The term battery also includes an intact, unbroken battery from which the electrolyte has been removed.

Waste Management Requirements for Small Quantity Handlers of Universal Waste Batteries:

(a) Universal waste batteries. A small quantity handler of universal waste must manage universal waste batteries in a way that prevents releases of any universal waste or component of a universal waste to the environment, as follows:

(1) A small quantity handler of universal waste must contain any universal waste battery that shows evidence of leakage, spillage, or damage that could cause leakage under reasonably foreseeable conditions in a container. The container must be closed, structurally sound, compatible with the contents of the battery, and must lack evidence of leakage, spillage, or damage that could cause leakage under reasonably foreseeable conditions.

(2) A small quantity handler of universal waste may conduct the following activities as long as the casing of each individual battery cell is not breached and remains intact and closed (except that cells may be opened to remove electrolyte but must be immediately closed after removal):

(i) Sorting batteries by type;

(ii) Mixing battery types in one container;

(iii) Discharging batteries so as to remove the electric charge;

(iv) Regenerating used batteries;

(v) Disassembling batteries or battery packs into individual batteries or cells;

(vi) Removing batteries from consumer products; or

(vii) Removing electrolyte from batteries.

(3) A small quantity handler of universal waste who removes electrolyte from batteries, or who generates other solid waste (e.g., battery pack materials, discarded consumer products) as a result of the activities listed above, must determine whether the electrolyte and/or other solid waste exhibit a characteristic of hazardous waste identified.

(i) If the electrolyte and/or other solid waste exhibit a characteristic of hazardous waste, it is subject to all applicable requirements . The handler is considered the generator of the hazardous electrolyte and/or other waste and is subject .

(ii) If the electrolyte or other solid wast

Waste Management Requirements for Large Quantity Handlers of Universal Waste Batteries:

(a) Universal waste batteries. A large quantity handler of universal waste must manage universal waste batteries in a way that prevents releases of any universal waste or component of a universal waste to the environment, as follows:

(1) A large quantity handler of universal waste must contain any universal waste battery that shows evidence of leakage, spillage, or damage that could cause leakage under reasonably foreseeable conditions in a container. The container must be closed, structurally sound, compatible with the contents of the battery, and must lack evidence of leakage, spillage, or damage that could cause leakage under reasonably foreseeable conditions.

(2) A large quantity handler of universal waste may conduct the following activities as long as the casing of each individual battery cell is not breached and remains intact and closed (except that cells may be opened to remove electrolyte but must be immediately closed after removal):

(i) Sorting batteries by type;

(ii) Mixing battery types in one container;

(iii) Discharging batteries so as to remove the electric charge;

(iv) Regenerating used batteries;

(v) Disassembling batteries or battery packs into individual batteries or cells;

(vi) Removing batteries from consumer products; or

(vii) Removing electrolyte from batteries.

(3) A large quantity handler of universal waste who removes electrolyte from batteries, or who generates other solid waste (e.g., battery pack materials, discarded consumer products) as a result of the activities listed above, must determine whether the electrolyte and/or other solid waste exhibit a characteristic of hazardous waste identified.

(i) If the electrolyte and/or other solid waste exhibit a characteristic of hazardous waste, it must be managed in compliance with all applicable requirements . The handler is considered the generator of the hazardous electrolyte and/or other waste and is subject .

(ii) If the electrolyte or other solid waste is not hazardous, the handler may manage the waste in any way that is in compliance with applicable federal, state or local solid waste regulations.

Fluorescent Lamps

Lamps such as fluorescent, neon, mercury vapor, high-pressure , sodium, metal halide, and high -intensity discharge are also examples of universal waste.

- Fluorescent bulbs:

- Linear, U-tube and circline fluorescent tubes

- Bug zappers

- Tanning bulbs

- Black lights

- Germicidal bulbs

- High output bulbs, and

- Cold-cathode fluorescent bulbs.

- High intensity discharge bulbs:

- Metal halide

- Ceramic metal halide

- High pressure sodium, and mercury vapor.

- Mercury short-arc bulbs; and

Important to Clean Up a Broken CFL Properly?

CFLs and the other light bulbs listed above contain a small amount of mercury sealed within the glass tubing. When a bulb breaks in your home, some of this mercury may be released as mercury vapor to minimize exposure to mercury vapor.

Aerosol Cans

Waste aerosol cans are managed as universal waste and no longer require hazardous waste labeling, requisitions, etc. These aerosol cans are primarily used in Facilities and Engineering divisions and contain paints, degreasers, lubricants, penetrants, glass cleaners, etc. Collection points for Engineering and Facilities staff have been identified; however, if you are outside of these organizations and have an aerosol can you wish to dispose of, contact your Generator Assistant or Waste Management for instructions. Note that aerosol cans with pesticides, herbicides, or catalysts cannot be managed as universal waste and must be submitted through the hazardous-waste requisition process.

Mercury-Containing Equipment

Unbroken thermometers, mercury-containing switches, thermostats, and other mercury-containing equipment should be placed in a container with packaging material to prevent breakage and labeled with a universal-waste label. A waste requisition is not required. Notify either your Generator Assistant or the Waste Management Group for pickup. Store in a safe location until pickup.

Labeling/Marking Requirements for Universal Waste Mercury-Containing Equipment:

A handler of universal waste must label or mark the universal waste to identify the type of universal waste as specified below:

(1) Universal waste mercury-containing equipment (i.e., each device), or a container in which the equipment is contained, must be labeled or marked clearly with any of the following phrases: “Universal Waste-Mercury Containing Equipment,” “Waste Mercury-Containing Equipment,” or “Used Mercury-Containing Equipment.”

(2) A universal waste mercury-containing thermostat or container containing only universal waste mercury-containing thermostats may be labeled or marked clearly with any of the following phrases: “Universal Waste-Mercury Thermostat(s),” “Waste Mercury Thermostat(s),” or “Used Mercury Thermostat(s).”

Special Wastes

Empty Containers

Certain empty containers that previously held hazardous materials are exempt from hazardous waste regulations and can be discarded as solid sanitary waste (trash) under the following conditions:

- The container must be <5 gallons in size.

- The container did not contain an

- extremely or acutely hazardous material.

- Without rinsing, the container contains no drainable or pourable liquid when held in any orientation.

- Without rinsing, the container contains no removable solids other than a thin, uniform layer of dried material or powder.

If your container meets the criteria listed above, the container may be thrown in the trash, and the following steps must be completed:

- The container must be deleted from the Chemical Management System, and the bar code must be removed from the container.

- The original label must be crossed out or marked with the word “EMPTY” to notify custodial staff, recyclers, or sanitary-waste engineers that it no longer contains hazardous materials, and can be discarded as solid sanitary waste.

Figure -6. The decision tree for the management of empty containers.

The decision tree shown below in Figure -6 can assist you in deciding how to properly dispose of your empty container.